A Consultative Approach

Determining the appropriate machinery and automation for each customer requires thoughtful conversation and a personalized approach

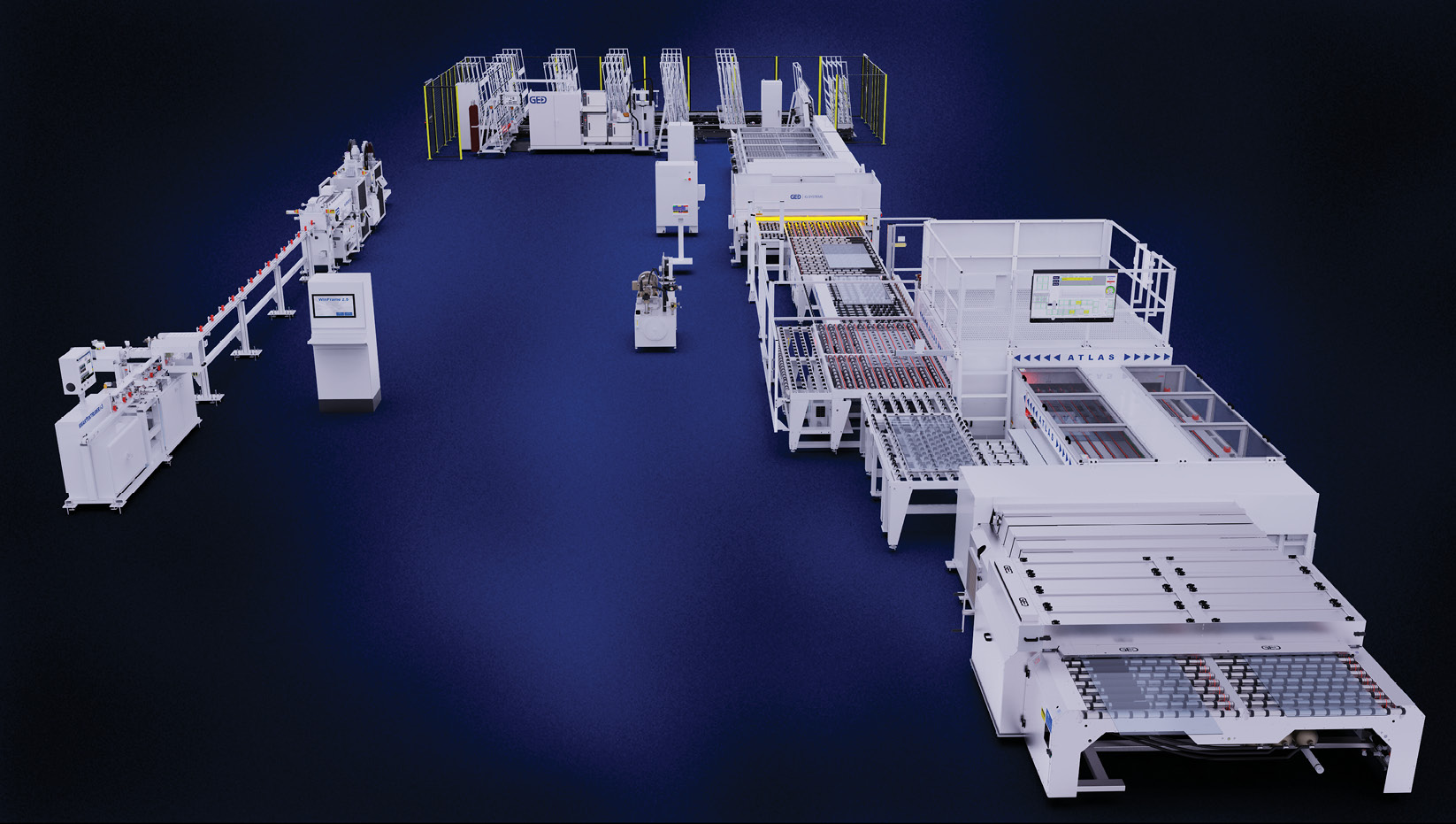

Above: Machinery manufacturers increasingly take on an advisory role with customers as they seek to understand their processes and pain points to recommend the best machinery and automation solutions. Photo courtesy of GED Integrated Solutions.

The right machinery begins with understanding. It’s critical to understand where bottlenecks exist, where labor gaps lie, what can be automated and what is best left to skilled labor and manual processes. The machinery manufacturer needs to understand their customer’s goals, and the customer needs to understand the capacity of what machinery and automation can do for their operation. That understanding leads to the right solutions.

What customers need … and don’t

Automation can range from simple to complex. The key is determining what the customer needs. GED Integrated Solutions’ tagline “Intelligent Automation” means finding the “appropriate mix of man and machine for the application,” says Joe Shaheen, vice president of sales, GED. Just because a machine can do myriad things doesn’t mean it’s what the customer needs. The company aims to understand its customers’ pain points, what they want to accomplish, and their labor pool’s capabilities and limitations.

Through those conversations, Shaheen says, his team can identify pain points, then suggest improved or even different processes. “The more of a consultative approach we take with our customers and the more they turn to us as a trusted advisor, the better we’re going to be in the long run,” he says. “We all have different knowledge and experiences. Let’s work together, form a partnership and make the whole process better.”

There are even times, he says, when automation isn’t the right answer. “In some cases, you just need something simple and quick,” he says. “Understand what the customer’s needs are and fit the right tool for the right application.”

Anthony Pigliacampo, CEO, Joseph Machine Co., agrees that understanding customers’ true needs is of utmost importance. “We try to understand each customer’s specific steps, the volume of those steps and the variations that occur within their product lines,” he says. “Then we help them select and design equipment that optimizes for that. What works for manufacturer A might not work for manufacturer B. For example, there are parts of the country where labor is both skilled and costs less than in other parts of the country. Fully automated solutions may work well in some markets, but in other markets the ROI is too high for it to make sense.”

Pigliacampo explains Joseph Machine’s process. “First and foremost is to understand what product they’re producing,” he says. The team then understands how the process is currently done, with what machinery, what is automated versus manual and where bottlenecks exist.

“Sometimes, there will be a single part of the production process that’s the actual bottleneck,” he says. “If we can understand that [part], it can dictate what automation you want to put ahead of it.” For example, if a glass line can produce only so much glass, it wouldn’t be appropriate to sell a piece of fabrication equipment that can produce double that amount of windows.

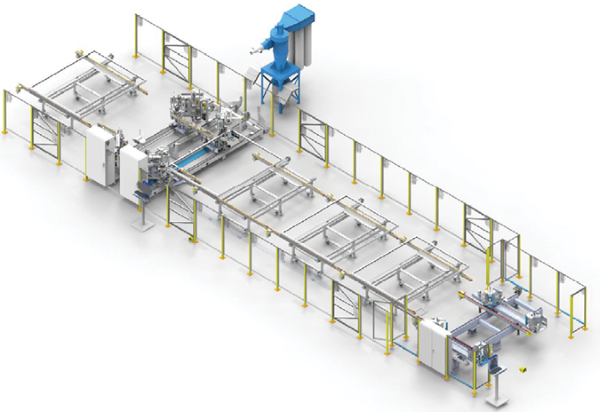

Pain points and processes are a huge part of the equation, but so are logistics. “You also have to look at the space they have,” says Brian Ludwig, North American sales manager, Erdman Automation, noting some high-speed machinery can be up to 150 feet long. Erdman tours a manufacturer’s facility to determine space, staffing, how many shifts they run, pre-processing equipment, storage capacity post-production, the company’s growth plans and more.

Sometimes, says Ludwig, the end result is they suggest a customer keep their current manual processes and invest in catching up on pre-process work and capacity. “We’re not going to suggest you buy our machine until we know you can support it from pre-processing, post-processing and maintenance,” he says. “It’s not just capacity. It’s not just sizing. There’s a whole-floor consideration. It’s about setting up each customer for long-term success in coordination with all the other machines and people they have.

“It’s very consultative,” he continues. “We work directly with our customers, especially the maintenance teams and plant managers, to understand pain points, align those with what products we have and share how we’d solve it.”

Labor

Machinery follows what Pigliacampo calls “a tide of capital equipment.” Since machinery is designed to last for quite a while, cycles happen where the machinery wears down and needs to be replaced. Today, he sees legacy equipment from the 1990s and early 2000s that’s difficult to support. “As the brains of the machine fail, manufacturers are unable to offer support, and it forces people to replace those.” That aging equipment, he says, creates opportunity in tandem with the labor shortage.

Customers look not only at what they need to replace but also examine where else they can improve processes. “There are certain jobs along the production line that are most problematic for staff,” he says. “If we can make those jobs easier and more repeatable with automation, those can get a high ROI.” Pigliacampo has also seen companies with two shifts implement higher throughput machines and get the same production rates working only one shift. “That becomes much easier for the customer to staff and justify the cost of automation,” he says.

Labor appears to be a long-term problem that requires long-term solutions. “I don’t think in my lifetime we’re going to have a situation where glass and vinyl goes in one end of the plant and windows come out the other end with nobody in the middle,” GED’s Shaheen says. “There’s going to be labor. There are going to be people. Our job, our challenge, is to best use the limited labor we have.”

Shaheen predicts the labor pool will get tougher and product volume will continue to grow in the U.S. “Because of that volume and our product, there’s still the need for selective and correct automation,” he says. “The challenge is to implement what we have and help our customers and also look at the next opportunity and areas where there isn’t machinery today. We have to get into the mindset of fewer people, fewer touches, fewer contact points and more automation. Not automation for the sake of automation, but identifying the real challenges customers have and taking steps to get there.”

Digital power

GED writes its own software, ties it into machines, which then can provide feedback about maintenance intervals or sense an upcoming problem to help with preventative maintenance. Shaheen likens it to a car’s check engine light. “It’s going to go on and your car doesn’t just typically stop and break right there, but if you ignore it for a month, you’re probably going to be in trouble. We use data feedback from our machines through our software to allow people to better understand preventative maintenance and generate better preventative maintenance procedures.”

Automated machinery can also catalog data from each component to allow for continuous tracking of performance parameters, says Pigliacampo. “We can look in detail at the performance of every component in a machine over time,” he says. “That allows us to find the weak links in machine designs.” Without that detail, he says, there’s no real way to determine what is causing an issue. For example, if a saw is drawing more current than what the acceptable band is, it will flag a warning on the machine and preventative maintenance can be performed.

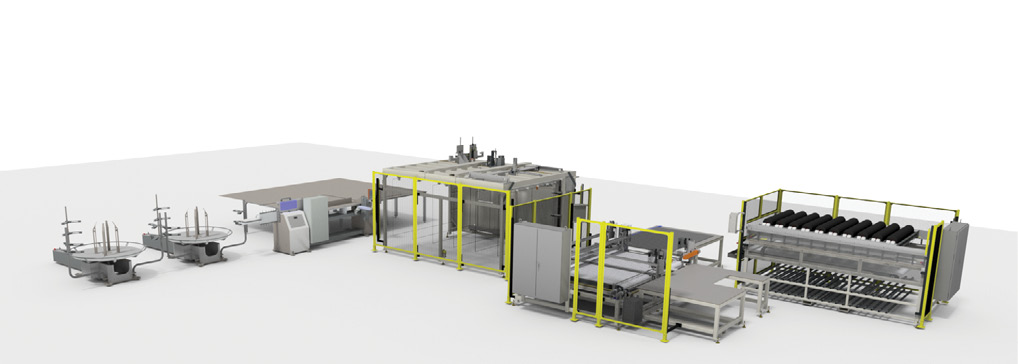

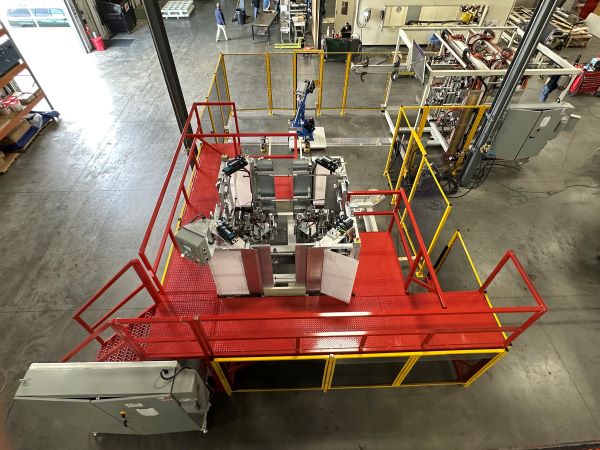

Joseph Machine has integrated digital twin technology into its operations, which can create fully interactive models of its machines before production even begins so the engineering team can simulate, test and optimize designs digitally. The process began about three years ago; the first step was to redesign control architecture so the system could interact with digital tools. Then, the company built machines with those systems built in. Finally, the past year has involved putting machines into the digital environment and using them effectively. “Our goal is to make this part of our standard design process,” Pigliacampo says. “It has a ton of potential, especially for highly automated solutions where the programming, setup and dialing everything in is what takes the most time. If you can do that offline in a virtual environment it can speed up the process.”

A stronger industry

Although the supply chain isn’t as dire as several years ago, tariffs and economic uncertainty have disrupted it somewhat. “The pandemic was a great dress rehearsal on what happens when supply chains don’t work as you think they might,” says Pigliacampo. “We spent a lot of time during that period, and immediately after, updating our architectures so we wouldn’t be held hostage by any one component.” Since Joseph Machine designs its components in-house, if one component becomes difficult to get, Pigliacampo is confident they can swap it for something equivalent.

Innovations continue in machinery. Erdman is developing a vertical vinyl window line to take the window in, cut the frame, weld it, clean it and glaze it. Ludwig estimates it will produce 1,000 single-hung windows per day and only require people for assembly at the end. The line has six robots and targets a 20- to 24-second cycle time. The company plans to debut a new technology at GlassBuild America in Orlando this fall that will increase speeds in TPS lines.

Efficiency takes many forms. Erdman is tackling it from a different perspective: that of having one machine to process myriad shapes and sizes, including thin-lite triples. Ludwig explains customers can program shapes they manufacture into a machine and feed the file with critical dimensions for that shape. Then, one machine will be able to manufacture most of their shapes, lessening a manufacturer’s efficiency concerns. “A valid part of this conversation is not only do you need to know cycle times and how many pieces you need per day, but also how much of your product can be done on one line,” he says.

Pigliacampo sees the industry not only embracing automation, but also lean manufacturing principles. “It’s really making the production of windows and doors more efficient,” he says.

“There’s a humungous opportunity to do more with less. To make windows and doors with less labor, less floor space and improve the quality. The market is getting to the point where they’re fully appreciating the benefit of these automated solutions. It makes our customers stronger. Some are really far down the road on leveraging automation to make their production better. They’re impressive to see and that’s great for American manufacturing.”